Without Words by Philip C. Barragan, II

The sound of our footsteps echoed through the hall. Dozens of faces too ill to smile stared at us as we tried not to look into their rooms. Hushed conversations mingled with the odors of Lysol, bleach and fresh flowers. We arrived at our destination. My mother asked for my handkerchief to dry her eyes. I reached out and held her hand like I did when I was child. We slowly entered his room and pulled the curtain around his bed pretending the other patient couldn’t hear us. The whispering oxygen machine and the heart monitor filled the background. My mother and I each took one of his hands. We asked him to squeeze if he could hear our voices. With all of his strength, he tightened his grip as tears began to flow down his cheeks. My father wouldn’t open his eyes for the rest of the afternoon.

He had spent a year recovering from surgery to remove the cancer from his throat. Inspecting old buildings for the City of Los Angeles exposed him to high levels of asbestos. He had to learn to speak all over again. I remember helping him walk while he was in hospital. He told the nurses “My son is all I need today.” His words were synthetic but sincere.

Within six months, he was back at work. The artificial larynx was removed and his words were less robotic and a little more human. We even went camping that summer trying to get back to ordinary family life. Everything appeared normal, but then his headaches started. He couldn’t stand and he couldn’t walk. He couldn’t get out of bed. He tried to drive home but he couldn’t stay on the road. The hidden cancer had crawled up his spinal cord, slipped into his brain and grew into several tumors.

The remaining months of my father’s life were rescinded to a few days, and possibly hours. The doctor told us that we had to decide on aggressive life support measures. I pulled my mother into another room for the most difficult discussion we ever had. She wanted to do everything possible to keep him alive. It’s a natural instinct. She didn’t want to live without him. He was all she knew.

* * *

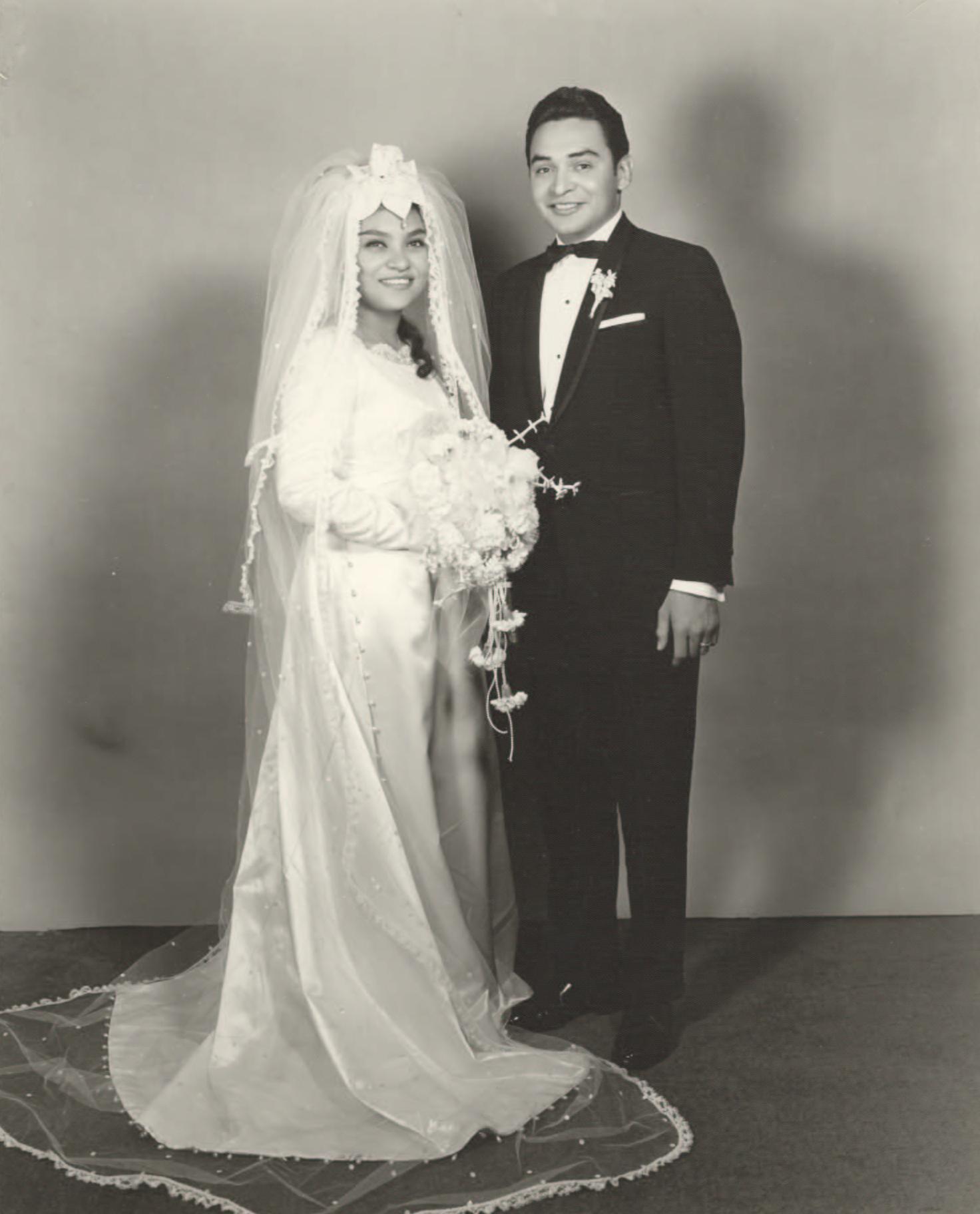

They met at a dance in 1960. She was twelve years old. My father was fifteen and played the trumpet for a band called The Gents. My mother frequently chaperoned her aunt Gloria who was five years her senior on dates and to dances on Saturday nights. All good girls had chaperones, and Gloria was very good. My mother sat in front of the band while Gloria danced all night. In a simple, plain dress and with her hair in an up-do, she could have passed for sixteen. Her beauty mark was exquisitely placed on her left cheek. It looked perfectly natural, just as Gloria taught her to do.

My father noticed the bright-eyed young girl watching him all night. He was entranced by her dark and dreamy eyes. She was so fresh, and so different from all of the other girls he knew. He played to her all night, and had to speak with her after the dance. Speaking wasn’t easy for him. He was very shy and often didn’t have the words to say what was in his heart. “My name’s Philip. I hope you can come see us next Saturday!” He’d look for her whenever his band played. And little Martha would be there, every time. Gloria was addicted to dancing and dragged her niece all over the Valley. Martha would always find a place to sit beside the stage and watch this young boy play his trumpet.

Against his mother’s wishes, they would marry five years later when she was seventeen and a senior in high school. Little Martha was the daughter of a 1950s divorcée; Mrs. Barragán would never give her consent for the marriage.

* * *

“Mom, he told us that he never wanted to be on life support.” She didn’t want to hear it. We didn’t realize he would be gone in a matter of hours. Years later my mother would tell me “I couldn’t believe you’d let him die without doing everything possible to keep him alive!” I told her we couldn’t allow him any more pain. That morning we watched him frantically waving his arm through the radiation chamber window. He just wanted it all to stop.

“Please make him as comfortable as possible,” we asked the doctor. Back in the room my father was non-responsive. I decided to call my grandparents, Grandma and Grandpa Bear. I told them “Dad was dying.” Within the hour, they arrived with his sister and six brothers like an army of barbarians capturing the city and holding the citizens hostage.

With the fierceness of a maniacal dictator, Grandma Bear began to shout orders. What to do, where to stand and how to pray. Being the young seminarian at the time, I was directed to lead the family in a series of prayers. I just wanted sit by my father. The room began to spin with feverish energy as his family raced around the bed beating their chests and reaching for heaven, reaching far and wide as if they were trying to catch a piece of Holy Spirit and devour it. I couldn’t remember the words to the prayers. My father was gasping for air. My mother tried to stay by his side but Grandma Bear slowly pushed her away from the bed while calling for the mercy and grace of God. I wanted it to end. I wanted the Bears to go away. The room became a modern day tent revival and the charlatan priestess had arrived.

* * *

Images filled my mind with the stories that my father used to tell us. Stories about his mother’s obsessive devotion to Christ and the Catholic Church. She would dress her children in shorts and take them to the park every Saturday. But before they were allowed to play, she’d make them kneel in the sand to pray the Rosary. She stood guard over them as they winced in discomfort. Their friends watched in the distance bewildered by what they saw. Mrs. Barragán was at it again. She pushed them deeper. Feeling the sand dig into their bare knees, they cried in silence. “M’hijos, feel the pain of Christ! He died for you!” She demanded compliance. She wanted everyone to see her display of religiosity. Completing the last “mystery” of the Rosary was their moment of release.

* * *

At 4:10 P.M. the monitor flatlined. There was no heartbeat. We were alone. Above the cacophony of unholy noise, I tried to shout to my mother “Dad was gone.” From across the room she read my lips and tried to scream but nothing come out. She collapsed. As she fell, her own spirit seemed to leave her body in search of her husband, her lover, her best friend. Only part of her returned to be with us. My Grandma Nina caught her lifeless body before she hit the floor. The remaining memories of that day become hazy and fragmented.

My father was a master dream maker and our lives have been forever changed without him. Wanton claims of greed were made by his family to explain his death. Continuous assaults of blame were cast towards my mother while Grandma Bear tried to extort money from the little we had. With the skill of a master surgeon, my mother excised his family from our lives.

We completed the many projects Dad left unfinished at home. “Every man’s home is his castle,” he used to tell us. And as long as he kept working on his castle, God would allow him the time to finish the task. During his recovery at home after the initial surgery, he had begun stripping the walls of the shiny gold and orange wallpaper trying to buy himself a little more time and another project to work on.

“Your husband was the smartest guy I know,” said Richard, one of his closest friends from work. Following the funeral a group of my father’s co-workers, engineers from the City, spent four weekends at my mother’s home completing the big master bedroom remodel that remained unfinished for thirteen years. During the construction, these men shared stories about their friend who was a very complex man. Someone who was driven to do a job right, and if you didn’t understand his direction, he’d just tell you to watch and “Imitate me,” and learn how to do it correctly. His way. The right way.

After the project was completed, Richard sat down with my mother and told her about a conversation he had with my father. On his last day of work, the two of them spoke about dying and my father’s deepest sorrow. Of everything he hated about dying so young, the most painful regret was that he wouldn’t be able to watch his children grow-up.

As I look at my nephew now, I can see my father’s reflection in his eyes and I hear his words as my brother Chris speaks with his son and our youngest brothers Matthew and Robert sharing the lessons we learned as children. My nephew is the same age as my father was when he met my mother forty-eight years ago at a dance hall in San Fernando. The image of that young boy playing his trumpet leaves me with a bittersweet memory and without the words to describe just how much I loved my father.

* * *

About the author:

Philip Charles Barragán II hails from the San Fernando Valley, California (the one and only valley). Born three years before the Summer of Love, always ahead of his time, Philip enjoys exploring his family roots and writing fiction and creative non-fiction in his almost non-existent free time. Philip spends his days working for the Office of AIDS Programs and Policy making the world a better place for individuals living with HIV/AIDS in Los Angeles County.

Philip Charles Barragán II hails from the San Fernando Valley, California (the one and only valley). Born three years before the Summer of Love, always ahead of his time, Philip enjoys exploring his family roots and writing fiction and creative non-fiction in his almost non-existent free time. Philip spends his days working for the Office of AIDS Programs and Policy making the world a better place for individuals living with HIV/AIDS in Los Angeles County.